The Prodigal Son: Grace That Offends and Love That Restores.

A Cultural, Linguistic, and Historical Reading of Luke 15:11–32

1. Setting the Scene: Why Jesus Told This Story

The Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11–32) does not stand alone. It is the third parable in a trilogy—after the Lost Sheep and the Lost Coin. Luke frames all three with the same provocation:

“Now the tax collectors and sinners were all drawing near to hear him. And the Pharisees and the scribes grumbled…” (Luke 15:1–2)

This matters deeply. As Alfred Edersheim repeatedly emphasized in The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah, Jesus’ parables often arise from Pharisaic murmuring rather than abstract theology. These stories are responses—sharp, pastoral, and confrontational.

In first-century Judaism:

Tax collectors were viewed as traitors and ritually compromised

“Sinners” (ἁμαρτωλοί, hamartōloi) referred not merely to moral failure but to people living outside Torah observance

Table fellowship implied acceptance and shared identity

Jesus is not merely telling a nice story about forgiveness. He is challenging the entire moral economy of his hearers.

2. A Shocking Request: “Give Me My Share” (Luke 15:12)

“Father, give me the share of property that is coming to me.”

Cultural Context (Edersheim)

In Jewish inheritance law (cf. Deut. 21:17), the firstborn received a double portion, but inheritance was normally distributed after the father’s death. For a son to demand it early was tantamount to saying:

“I wish you were dead.”

Edersheim notes that such a request would have brought public shame upon the father. In a culture where honor was communal, not individual, this was not a private family spat—it was a village scandal.

Greek Insight

οὐσία (ousia) – “substance,” “being,” or “estate”

This word goes deeper than “money.” The son is asking for the father’s life, his accumulated identity and legacy.

The father’s response is astonishing:

“And he divided his life (bios) between them.”

The Greek emphasizes the father’s self-giving loss. This is not indulgence—it is costly love.

3. Far Country, Empty Soul (Luke 15:13–16)

“He squandered his property in reckless living.”

Greek Insight

ἀσώτως (asōtōs) – “wastefully,” “without saving,” “dissolutely”

From this word we get asōtia—a life with no orientation, no telos.

This is not just moral failure; it is existential unraveling.

Cultural Depth

The “far country” is not merely geographical. In Jewish imagination, distance from the land often implied:

Distance from covenant

Distance from purity laws

Distance from God’s protective presence

The famine that follows is not accidental. In biblical thought, famine often accompanies covenantal dislocation.

Then comes the lowest point:

“He longed to be fed with the pods that the pigs ate.”

Pigs were ritually unclean (Lev. 11:7). Edersheim points out that feeding pigs would have been unthinkable employment for a Jew. Jesus is deliberately pressing the image to its most degrading extreme.

4. “He Came to Himself” (Luke 15:17)

“But when he came to himself…”

Greek Insight

εἰς ἑαυτὸν δὲ ἐλθὼν (eis heauton de elthōn)

Literally: “He came into himself.”

This is not mere regret—it is awakening. In Jewish wisdom literature, repentance (תשובה, teshuvah) begins with remembering who you truly are.

The son rehearses a confession:

“I am no longer worthy to be called your son.”

Greek Insight

ἄξιος (axios) – “worthy,” “deserving,” “having weight”

He understands that he has forfeited honor. What he does not yet understand is the nature of the father’s love.

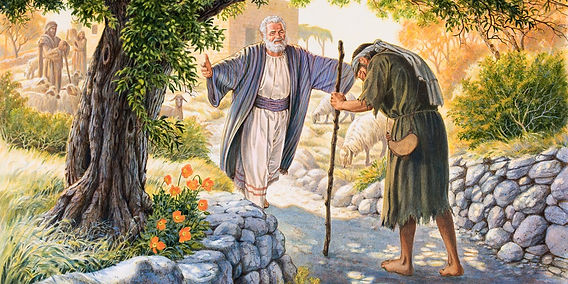

5. The Father Runs (Luke 15:20)

“But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion.”

Cultural Shock (Edersheim)

Middle Eastern patriarchs did not run. Running required:

Lifting one’s robe (exposing legs)

Public self-humiliation

Loss of dignified composure

Edersheim stresses that this action would have shocked Jesus’ audience more than the son’s rebellion.

Greek Insight

ἐσπλαγχνίσθη (esplagchnisthē) – “he was moved with compassion”

From splagchna, the inner organs. This is visceral, gut-level mercy.

The father:

Runs

Embraces

Kisses repeatedly (κατεφίλησεν, katephilēsen)

The son never finishes his rehearsed speech. Grace interrupts him.

6. Bring Out the Best Robe”: The Father Dresses the Son (Luke 15:22)

“But the father said to his servants, ‘Bring quickly the best robe, and put it on him, and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet.’”

This moment is not decorative—it is theological theater. In a shame–honor culture, clothing communicates status, identity, and belonging. The father does not merely welcome the son home; he re-clothes him into sonship.

The Best Robe: Restored Honor

The phrase “best robe” is not simply about quality.

Greek Insight

στολὴν τὴν πρώτην (stolēn tēn prōtēn)

Literally: “the first robe” or “the chief robe”

This suggests a robe of preeminence, likely one reserved for the father himself or for honored guests. In Edersheim’s cultural framework, such a garment would have been worn on festive or ceremonial occasions, not daily labor.

To robe the son publicly means:

His shame is covered, not discussed

His past is not negotiated

His status is immediately restored

This echoes a deep biblical theme: God restores by clothing.

Adam and Eve are clothed by God after their failure (Gen. 3:21)

Joshua the High Priest is given clean garments after accusation (Zech. 3:3–5)

Isaiah rejoices in being “clothed with garments of salvation” (Isa. 61:10)

The robe declares: “You are no longer defined by where you have been.”

The Ring: Authority and Belonging

The father next commands:

“Put a ring on his hand…”

Greek Insight

δακτύλιον (daktylion) – “signet ring”

This is not jewelry. In the ancient world, a signet ring represented:

Legal authority

Family identity

The right to act in the father’s name

Edersheim notes that such rings were used to seal documents and conduct business. To give the son a ring is to trust him again, publicly and without probation.

This is radical. The son had intended to ask for servanthood. Instead, he is entrusted with authority.

Grace does not merely forgive the past—it re-empowers the future.

Sandals: From Slavery Back to Sonship

“And shoes on his feet.”

This detail is easy to overlook—and deeply important.

In the ancient household:

Slaves went barefoot

Sons wore sandals

The father is explicitly rejecting the son’s proposed identity:

“Make me like one of your hired servants.”

He will not allow the son to define himself by penance rather than relationship.

The sandals proclaim:

“You do not work your way back into this family. You belong.”

A Public Reversal of Shame

Taken together, the robe, ring, and sandals function as a ritual of restoration.

Edersheim highlights that such actions would have occurred before the village, not in private. This matters because, in Near Eastern culture, shame was communal. Without the father’s public intervention, the son could have faced:

Social exclusion

Mockery

Even a kezazah ceremony (a traditional cutting-off of a disgraceful son)

By clothing him immediately, the father preempts rejection. He absorbs the shame so the son does not have to.

Theological Meaning: Justification Before Sanctification

The father clothes the son before:

Any explanation

Any restitution

Any moral improvement

This is a narrative picture of what later theology would call grace preceding transformation.

The son is not restored because he has changed.

He begins to change because he is restored.

Practical Reflection

Many people are willing to believe God forgives them.

Far fewer believe He restores their dignity.

Yet this parable insists:

God does not keep returning sinners in spiritual rags

He does not mark them as “former failures”

He clothes them as sons and daughters again

To refuse the robe is, in its own way, to stand outside the feast.

7. The Elder Brother: The Real Target

The story could have ended at verse 24. It doesn’t—because Jesus is not finished addressing the Pharisees.

The elder brother:

Obeys

Stays

Works

Yet he speaks like a slave:

“These many years I have served you…”

Greek Insight

δουλεύω (douleuō) – “to serve as a slave”

He has proximity to the father but no intimacy with him.

Edersheim often notes that Pharisaic religion, at its worst, replaced sonship with servitude. The elder brother cannot rejoice because he believes love must be earned.

The father’s response is gentle, not harsh:

“Son (teknon), you are always with me.”

The tragedy is that the elder brother is lost at home.

8. Theological Heart: A Father Who Bears Shame

At its core, this parable reveals:

A father who absorbs dishonor

A love that precedes repentance

A grace that offends moral accountants

Jesus is redefining righteousness—not as separation from sinners, but as self-giving love that restores them.

In Edersheim’s framework, this parable encapsulates Jesus’ re-centering of Israel’s hope: not around boundary-marking holiness, but around redemptive mercy.

9. Practical Conclusions: Living Inside the Parable

1. Repentance Is Returning, Not Groveling

True repentance is not self-hatred—it is remembering where home is.

2. God’s Grace Will Offend Your Sense of Fairness

If grace feels “unfair,” you’re probably understanding it correctly.

3. You Can Be Near God and Still Miss His Heart

Religious activity does not guarantee relational intimacy.

4. Restoration Is Public, Not Private

God does not merely forgive in secret—He restores identity and joy.

Final Thought

The Parable of the Prodigal Son is not about which brother you are.

It is about what kind of Father God is.

A Father who runs.

A Father who absorbs shame.

A Father who invites both rebels and rule-keepers into the same feast.

And the story ends unfinished—because the final response belongs to us.

Leave a comment